There is almost no need to explain why equal opportunities in education are essential for social mobility. But an equal budget isn’t equivalent to equal opportunity; enabling a child with a low starting point to succeed in school requires a bigger investment – more school hours, better teachers and so on.

In Israel, however, this is not the case. Although underprivileged students enjoy some preference in the public education budget, it is not substantial enough to close existing gaps. Moreover, affluent municipalities often cause the gaps to grow larger when they invest additional resources in local schools.

A differential budgeting system, recommended by several public commissions, was adopted by the Israeli Ministry of Education in 2014. Its model focused on allocation of extra teaching hours in elementary and junior high schools, reasoning that this has a direct and immediate impact on the students. The allocation was based on the “deprivation index” (also called ‘nurture index’) of the school, calculated by factors such as the level of education and income of the students’ parents and their country of origin.

This model doesn’t include kindergartens and high schools, nor take into account any aspect of education beyond formal teaching hours. In addition, the differential budget is allocated per school according to the socioeconomic resilience of its student body, but regardless of its location. Thus, a weak school in Tel Aviv gets the same budget as a weak school in Rahat, a poor Bedouin town. This, despite the fact that one school can get supplementary funding from municipal resources and the other can’t.

Extending the differential budgeting to all levels of education and all components of the budget is one of the main recommendations of the policy brief drafted as part of Rashi’s Springboard to Social Mobility plan.

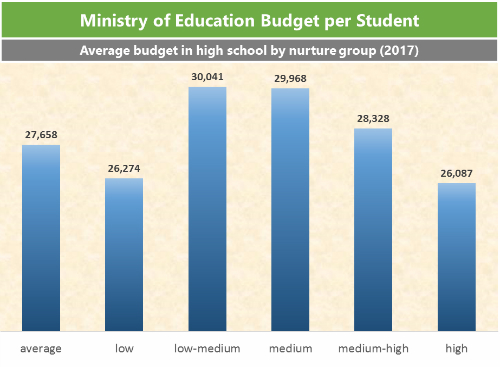

In high school, for example, instead of getting more state funds, weaker schools may actually get less. Ministry of Education figures show, in fact, that students in the highest and lowest socioeconomic groups get practically the same budget (see graph below).

Changing the budgeting system of kindergartens to take into consideration the children’s background is also critically important, because of the great significance of early childhood education for social mobility, as we saw in this post.

Another issue requiring a different allocation of resources is special classes for advancing low-achieving students. The need is particularly acute in small communities that get no budget at all since they don’t meet the criteria with regard to the minimum number of eligible students.

Finally, differential budgeting should be extended to include informal education and gap year programs. Both fields offer many opportunities for social mobility by enabling children, youth and young adults to develop valuable skills and acquire tools that will benefit them throughout life.