The World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland is not usually associated with discussions of inequality gaps or socioeconomic mobility. But the WEF Global Social Mobility Report 2020, published ahead of this year’s meeting, ranks 82 countries worldwide according to their success in providing opportunities for their citizens to move up the social-economic ladder, based in a new index measuring mobility.

Klaus Schwab, WEF Founder and Chairman, writes in the preface to the report: “The social and economic consequences of inequality are profound and far-reaching: a growing sense of unfairness, precarity, perceived loss of identity and dignity, weakening social fabric, eroding trust in institutions, disenchantment with political processes (…) The response by business and government must include a concerted effort to create new pathways to socioeconomic mobility, ensuring everyone has fair opportunities for success.”

The Forum’s interest in socioeconomic mobility is part of a noticeable trend in recent years of international institutions looking into issues of social gaps and inequalities; one of the main reasons for this is the strong connection of these issues to economic growth and prosperity.

The main – and not very encouraging – finding of the report is that only a handful of countries have the right conditions to foster social mobility; this means that most people are “stuck” in the socioeconomic class into which they were born, and that the disparities persist and even grow deeper.

Measuring social-economic mobility: a new approach

So what exactly is new about the new global mobility index? The common approaches for measuring mobility, i.e. by comparing the earnings of children and their parents, show the results of the conditions that prevailed 30-40 years ago. The WEF index, on the other hand, analyzes the current situation in order to predict the future of today’s children.

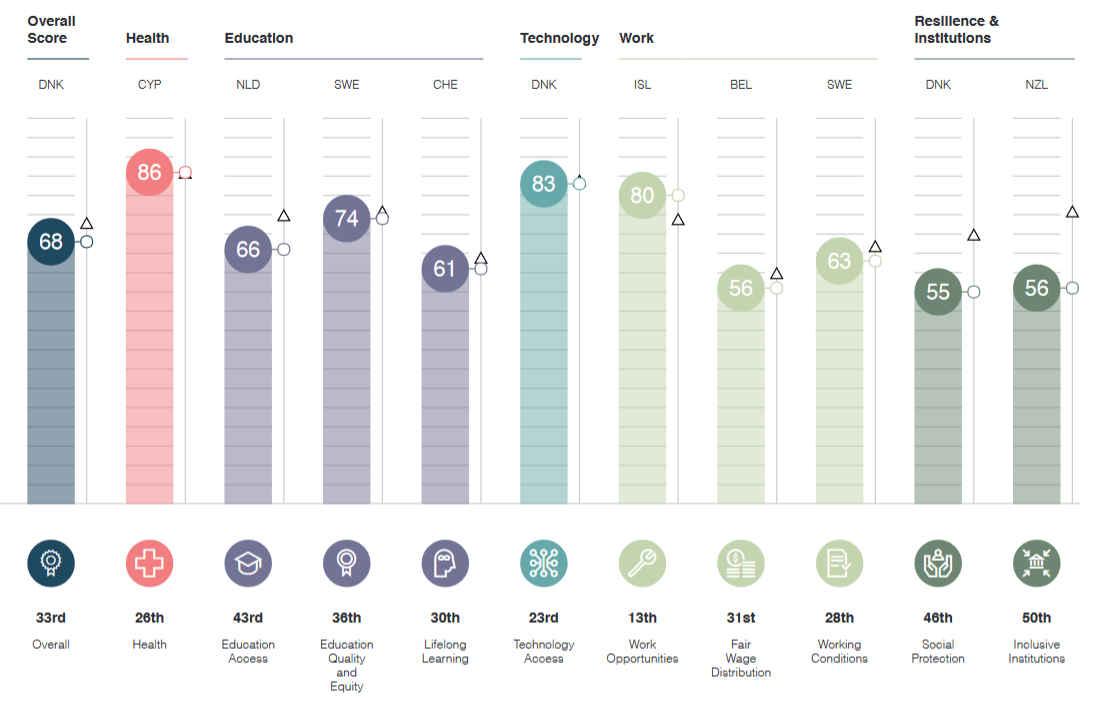

Instead of after-the-fact outcomes, the global social mobility index focuses on factors – policies, practices and institutions – that influence mobility and therefore determine the outcomes we will see in the coming decades. The index estimates the combined impact of some 50 factors in the fields of health, education, technology access, work and social resilience. These factors include, for example: enrollment in pre-primary education; pupil-teacher ratio in different levels of education; prevalence of malnourishment among children; rate of young adults not in education, training or employment; percentage of workers earning low wages; and so on.

Social mobility, country by country

Globally, the greatest challenges that the report identified are low wages, lack of social protection and poor lifelong learning systems – critical issues in which most countries received low scores. The Nordic countries (Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden and Iceland) were the best performers overall, while Israel ranked 33rd out of 82. However, when looking only at the group of high-income economies, our ranking is still 33 – but out of 41, which is somewhat less reassuring.

As you can see in the graph above, Israel’s strengths are in its health system, access to technology and work opportunities. Still, there is a lot of room for improvement, especially with regard to social protection, fair wage distribution and inclusive institutions.

As you can see in the graph above, Israel’s strengths are in its health system, access to technology and work opportunities. Still, there is a lot of room for improvement, especially with regard to social protection, fair wage distribution and inclusive institutions.

The cost of missed opportunities

In order to make the impact of social mobility more tangible, the report makes an estimate of the economic ‘cost of missed opportunities’ due to lack of social mobility, by calculating the effect of mobility on economic growth in dollar terms.

The result: If all countries improved their social mobility index score by 10 points, the extra growth of the global economy would translate into $514 billion each year, or an increase of 4.4% in the global GDP by 2030 – all in addition to vast social cohesion benefits.